We found a wide range of fossils including, a fossil shark’s tooth, bivalve shells, belemnites and amazing ammonites. We found out about these wonderful creatures that lived in the semi-tropical seas that covered Kent over 65 million years ago. And we discovered medieval stories about them too, including the legend of St Hilda, who turned serpents to stone!

With spectacular views of the White Cliffs, we enjoyed a picnic on the beach and chatted and relaxed. People were having so much fun they didn’t want to leave.

The walk down to the beach, called Folkestone Warren is on steep paths, which can be slippery when wet, with large steps at the bottom, then across a stony beach (with some large boulders). The beach was quite slippery with seaweed, and although we went quite slowly, we still probably walked a couple of miles.

The fossils are in a bank of soft sticky clay so old clothes and wellies were essential. It wasn’t very sunny, but the rain held off, so we didn’t need waterproofs. But we did need a huge bag for the fossils!

We met at 10 am on the grass next to the children’s play area, on Wear Bay Road, adjacent to the bowling green at East Cliff Sports. We walked down the steep cliff path with giant steps – thinking that every step was taking us back a million years until we reached the bottom of the cliff where the fossils are found.

And we found loads!

We found a wide range of fossils including, a fossil shark’s tooth, bivalve shells, belemnites and amazing ammonites. We found out about these wonderful creatures that lived in the semi-tropical seas that covered Kent over 65 million years ago. And we discovered medieval stories about them too, including the legend of St Hilda, who turned serpents to stone!

With spectacular views of the White Cliffs, we enjoyed a picnic on the beach and chatted and relaxed. People were having so much fun they didn’t want to leave.

The walk down to the beach, called Folkestone Warren is on steep paths, which can be slippery when wet, with large steps at the bottom, then across a stony beach (with some large boulders). The beach was quite slippery with seaweed, and although we went quite slowly, we still probably walked a couple of miles.

The fossils are in a bank of soft sticky clay so old clothes and wellies were essential. It wasn’t very sunny, but the rain held off, so we didn’t need waterproofs. But we did need a huge bag for the fossils!

We met at 10 am on the grass next to the children’s play area, on Wear Bay Road, adjacent to the bowling green at East Cliff Sports. We walked down the steep cliff path with giant steps – thinking that every step was taking us back a million years until we reached the bottom of the cliff where the fossils are found.

And we found loads!

How Medieval People thought about Fossils

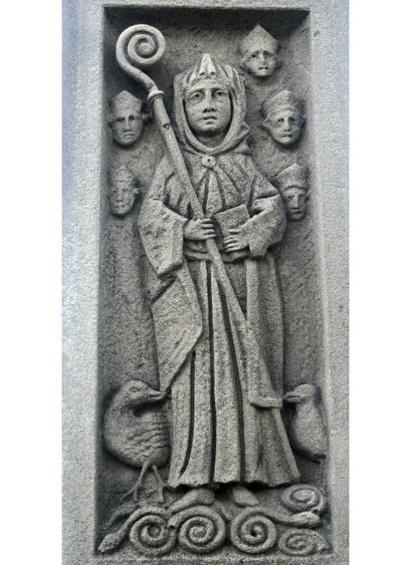

Besides the legend of St Hilda turning snakes into stones, (see her on the left, from her monument in Whitby) there’s a story about St Augustine of Hippo finding a fossil.

St Augustine lived in the fifth century in Africa. One day, he was walking along a beach in Utica, in what is now Tunisia, when he found a huge fossil tooth. Augustine wrote about his find, saying he thought it was a giant’s tooth from a long time ago – and that it was bigger than a hundred human molars (City of God, Bk. 15 ch.9). Modern palaeontologists think the fossil tooth may have come from a mammoth or a mastodon. Here’s a mammoth tooth from the Beaney Institute in Canterbury (above, c. 30 cm long).

Some early twentieth century palaeontologists thought ancient and medieval people believed fossils were merely interestingly shaped or patterned stones that only looked like animals or plants. But there is evidence that at least some premodern people thought fossils were originally living plants and animals, even if, like St Augustine, they thought they were from giants rather than ancient mammoths or mastodons. As today, there were different opinions – but without the body of scientific knowledge we have now. For example, the bestiary (a medieval book of beasts) stated that amber came from the urine of the Lynx (a large wild cat – see the medieval drawing below from the Bestiary of Ann Walsh, now in Copenhagen). Yet St Isidore of Seville (who died in 636) wrote that ‘amber…. is formed in the islands of the Northern Ocean as pine gum and is solidified like crystal by cold or by the passage of time.’ (Etymologies, Bk 16, ch. 8.7).

Avicenna (Ibn Sina d. 1037) the famous Islamic doctor and philosopher, wrote:

Mountains have been formed by one of the causes of the formation of stone, most probably from agglutinative clay which slowly dried and petrified during ages of which we have no record. It seems likely that this habitable world was in former days uninhabitable and, indeed, submerged beneath the ocean… It is for this reason that in many stones, when they are broken, are found parts of aquatic animals, such as shells, etc. (De congestione et conglutinatione lapidum, trans. E. J. Holmyard, p. 28). and Albert Magnus (d. 1280) also wrote about how fossils were formed:

The cause of this is that animals, just as they are, are sometimes changed into stones. . .and the parts of the body retain their shape, inside and outside, just as they were before.

(Book of minerals, I.ii.8, trans. D. Wyckoff, p. 52).

There has always been interest in fossils – and there is still a great deal more to discover.

Diane Heath

Further Reading:

D. Badke, on Lynx ‘amber’, see the Medieval Bestiary (illustration: Bestiary, Copenhagen, KB, Ms GKS 1633 4o, fol. 6)

M. Carnall, on The ancient mystery of St Hilda’s ‘snake stones’, Guardian 14.6.2017

M. Crowther, Rocks and Fossils, Folkestone Museum (fmlearnwithobjects.co.uk)

P. Eyden (2004), ‘Folkestone Fossil Beds’, Folkestone Fossil Beds | The Octopus News Magazine Online (tonmo.com)

P. Hadland, Fossils of Folkestone (2018)

J. M. Jordan (2016), “Ancient episteme’ and the nature of fossils: a correction of a modern scholarly error,’ History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 38(1), 90–116. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44744598

K. Lotzof, Snakestones: the myth, magic and science of ammonites, (Natural History Museum website)

J. McGowan-Hartmann (2013) ‘Shadow of the Dragon: The Convergence of Myth and Science in Nineteenth Century Paleontological Imagery’, Journal of Social History, 47(1), 47–70.http://www.jstor.org/stable/43306045